Let’s practice the passato prossimo. Quick review and quiz

This is just a review, so I am assuming you are already familiar with the passato prossimo regolare.

The quiz at the bottom of this page is a basic review with some new vocabulary. Look up the words and verbs you don’t know.

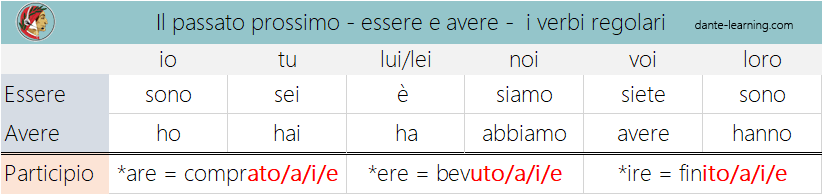

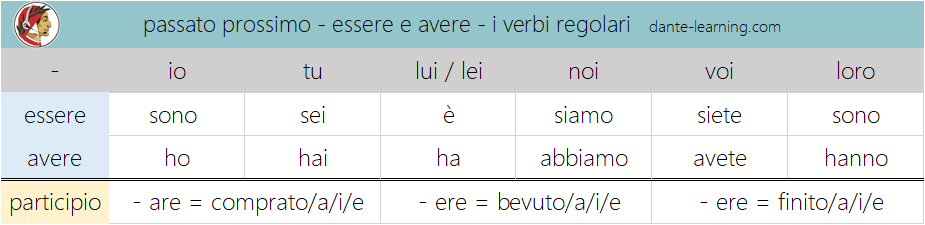

In a nutshell, the Passato Prossimo:

- Describes a complete action in the past.

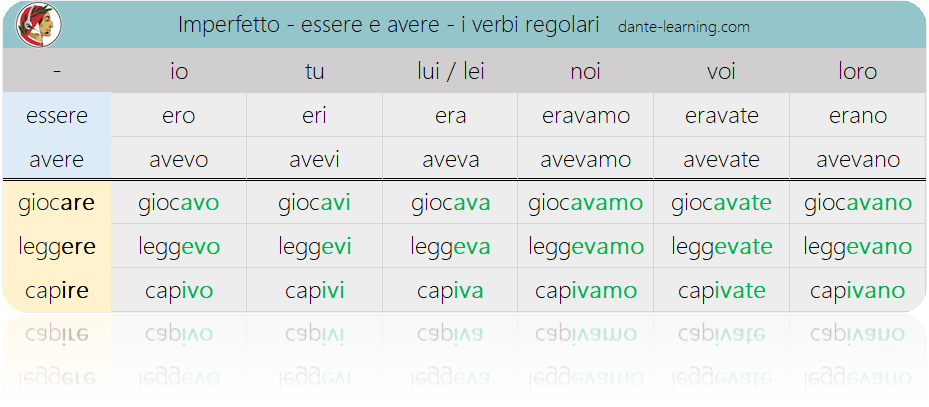

- The passato prossimo regolare is the combination of essere and avere + past participle (ato-uto-ito):

Ieri …

- … sono andato a scuola. –> I went to school.

- … ho mangiato il minestrone. –> I ate minestrone.

If you have doubts about essere or avere as auxiliary verbs, please practice with this exercise.

Don’t forget to check your score at the end of the quiz.

Quiz-summary

0 of 4 questions completed

Questions:

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Information

LOADING QUIZ...

You have already completed the quiz before. Hence you can not start it again.

Quiz is loading...

You must sign in or sign up to start the quiz.

You have to finish following quiz, to start this quiz:

Results

Time has elapsed

Your score is 0 out of 0 points, (0)

| Average score |

|

| Your score |

|

Categories

- Not categorized 0%

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- Answered

- Review

-

Question 1 of 4

1. Question

With avere, regular verbs

e.g. - Io e la mia famiglia (abitare) abbiamo abitato a Roma per un anno

-

- Mio padre (vendere) (ha venduto) la macchina vecchia e (comprare) (ha comprato) una moto.

- Io e mia moglie (prenotare) (abbiamo prenotato) una camera d'albergo a Modena.

- Mia sorella (cucinare) (ha cucinato) e io (lavare) (ho lavato) i piatti.

- Se voi (comprare) (avete comprato) un computer usato, non (risparmiare) (avete risparmiato) molti soldi.

- Il mese scorso io (pagare) (ho pagato) le tasse.

- I miei figli non (fumare) (hanno fumato) mai una sigaretta in vita loro.

- Camminando per strada, stamattina Francesca (trovare) (ha trovato) venti euro.

- I miei colleghi (lavorare) (hanno lavorato) per tutta la notte e (finire) (hanno finito) stamattina alle sei.

- Il mio cane (sporcare) (ha sporcato) il pavimento e mio marito (pulire) (ha pulito).

- Ieri sera noi (mangiare) (abbiamo mangiato) i peperoni ripieni ma non (digerire) (abbiamo digerito).

- Per il matrimonio di Andrea, le ragazze (indossare) (hanno indossato) degli abiti meravigliosi.

- Gli studenti (capire) (hanno capito) il passato prossimo ma non (studiare) (hanno studiato) abbastanza.

- Perché voi (usare) (avete usato) il computer di Davide senza il suo permesso?

- Mia madre (guidare) (ha guidato) tutto il giorno per venire al mare da noi.

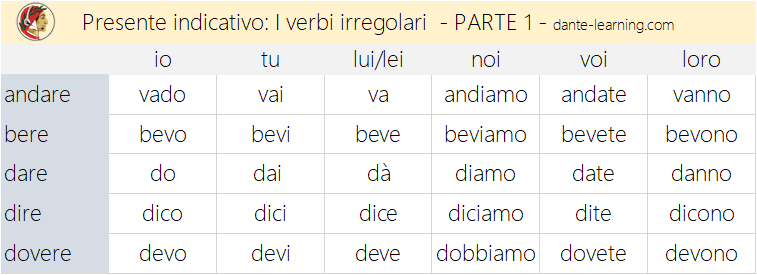

- Quei signori anziani al bar (bere) (hanno bevuto) due bottiglie di vino e non (mangiare) (hanno mangiato) niente.

Correct

In red your errors, in green the correct choices.

Incorrect

In red your errors, in green the correct choices.

-

-

Question 2 of 4

2. Question

Con il verbo essere

-

- Gli studenti ieri (andare) (sono andati) al museo.

- Le mie amiche (arrivare) (sono arrivate) a casa nostra.

- Ieri noi (uscire) (siamo usciti) ma faceva freddo e (tornare) (siamo tornati) a casa presto.

- Io e Graziella abbiamo fatto una dieta e (dimagrire) (siamo dimagriti).

- Le vacanze (iniziare) (sono iniziate) ieri.

- Noi oggi (partire) (siamo partiti) per il mare e i nostri vicini (tornare) (sono tornati) ieri.

- Abbiamo organizzato una festa e (venire) (sono venuti) tutti i nostri amici.

Correct

In red the errors, in green the correct answers.

Incorrect

In red the errors, in green the correct answers.

-

-

Question 3 of 4

3. Question

Essere o Avere?

-

- Io e il mio cane (camminare) (abbiamo camminato) al parco tutto il pomeriggio.

- I tuoi nonni (passeggiare) (hanno passeggiato) in riva al mare.

- Federico e Manuela (divorziare) (hanno divorziato) l'anno scorso.

- Le regole dell'economia (cambiare) (sono cambiate) molto negli ultimi anni.

- Noi (comunicare) (abbiamo comunicato) al comune di Milano il nostro nuovo indirizzo.

- Le patatine (finire) (sono finite). Se tu (finire) (hai finito) di lavare i piatti, puoi aprire un altro pacco?

- Io (capire) (ho capito) la lezione sul passato prossimo ma non (studiare) (ho studiato) i nuovi verbi.

Correct

In red the errors, in green the correct answers.

Incorrect

In red the errors, in green the correct answers.

-

-

Question 4 of 4

4. Question

Ancora essere o avere.

-

- Tu (provare) (hai provato) il risotto con le fragole?

- Noi non (riuscire) (siamo riusciti) a trovare il ristorante quindi (arrivare) (siamo arrivati) tardi.

- La mia famiglia (preparare) (ha preparato) una festa a sorpresa per il mio compleanno.

- Le bambine (giocare) (hanno giocato) a calcio e (conoscere) (hanno conosciuto) delle nuove amiche.

- Voi (visitare) (avete visitato) la pinacoteca di Brera a Milano? Noi ci (andare) (siamo andati) l'anno scorso.

- Mia mamma (lavare) (ha lavato) il maglione rosso con le lenzuola, che (diventare) (sono diventate) rosa.

- (io - sapere) (ho saputo) che (finire) (sono finiti) i biglietti per il concerto di Vasco Rossi.

Correct

[list icon="lightbulb" color="blue"]

-

In red the errors, in green the correct answers.

Incorrect

[list icon="lightbulb" color="blue"]

-

In red the errors, in green the correct answers.

-

Silvestro Lega “Ragazza di Crespina” XIX sec.