The Italian Passato Prossimo describes actions and events set in the recent and far past

Theoretically, the Italian Passato Prossimo should describe actions and events with a beginning and an end set in the recent past (Passato Prossimo means “near” past), with a logical connection with the present.

In reality the Passato Prossimo, in modern Italian, can describe any complete event set in the past. Even when the action is not close to the present.

We should use the Italian Passato Remoto when an action has no connection with the present. However as described more properly in this post about the Passato Remoto, the limited use of the Italian Passato Remoto among Northern Italian speakers and the role of the Passato Prossimo in the media, makes the latter a preferred choice in the spoken language. That said, let’s see how the Passato Prossimo works.

- Oggi sono andato al cinema.

- L’anno scorso ho comprato un telefono.

The Italian Passato Prossimo is a compound tense. It looks like the English Present Perfect (I have eaten) but the concept is closer to the Simple Past (I ate).

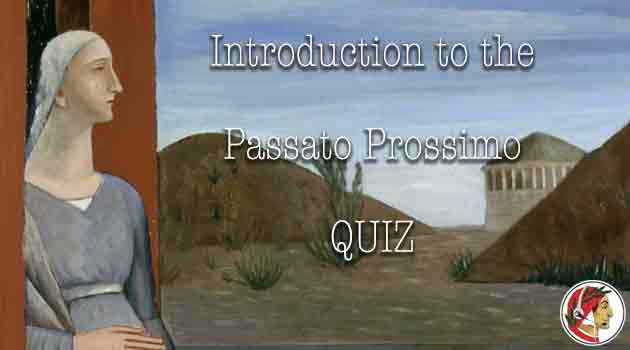

Very briefly, we can notice a few important things about the Passato Prossimo.

- It’s built with the present tense of essere or avere and the past participle of the main verb (–ato, –uto, –ito).

- Most Italian verbs use avere in the Passato Prossimo (green chart). In this case, the past participle generally doesn’t change (–ato, –uto, —ito). There are important exceptions, for example when we use direct object pronouns, but for simple Passato Prossimo the participle doesn’t change according to the subject.

- In many important cases, we need to use essere (orange chart). If so, the past participle does change in accordance to the subject, singular, plural, masculine and feminine.

- In some cases, verbs can use both essere or avere (il film è finito VS ho finito i soldi) with the Passato Prossimo, depending on the subject or the object of the sentence. We can talk about that in our Skype classes, but those are exceptions and you should treat them as such.

Avere

| comprare | sapere | capire | |

|---|---|---|---|

| io | ho comprato | ho saputo | ho capito |

| tu | hai comprato | hai saputo | hai capito |

| lui | ha comprato | ha saputo | ha capito |

| lei | ha comprato | ha saputo | ha capito |

| noi | abbiamo comprato | abbiamo saputo | abbiamo capito |

| voi | avete comprato | avete saputo | avete capito |

| loro | hanno comprato | hanno saputo | hanno capito |

Essere

| tornare | crescere | vestirsi | |

|---|---|---|---|

| io | sono tornato/a | sono cresciuto/a | mi sono vestito/a |

| tu | sei tornato/a | sei cresciuto/a | ti sei vestito/a |

| lui | è tornato | è cresciuto | si è vestito |

| lei | è tornata | è cresciuta | si è vestita |

| noi | siamo tornati/e | siamo cresciuti/e | ci siamo vestiti/e |

| voi | siete tornati/e | siete cresciuti/e | vi siete vestiti/e |

| loro | sono tornati/e | sono cresciuti/e | si sono vestiti/e |

When we use Essere

In some books you will read that essere is used with intransitive verbs, that cannot have an object. For example andare —> Sono andato al cinema.

True, andare is intransitive, it doesn’t answer the question “what?” or “who?”, but rather “dove?” etc.

I find it rather misleading. Many intransitive verbs combine with avere (e.g. Ho dormito), so we have to narrow down the cases where essere is our auxiliary verb.

- With verbs of movement, usually from and to a place, such as andare, venire, entrare, uscire, tornare, salire, scendere, cadere etc.

- With verbs of position: stare, restare, rimanere…

- With verbs representing a change: ingrassare, dimagrire, crescere, nascere, morire, diventare…

- All reflexive verbs: vestirsi, prepararsi, divertirsi sposarsi…

- Verbs like piacere, mancare, servire…

- Passive and impersonal: il libro è stato scritto, ieri ci si è divertiti …

When we use Avere

When a verb supports an object. In other words, if you ask the question Who? or What? and get an answer. They are called “transitive” verbs. It’s an oversimplification but it works.

- Ho comprato (cosa?) un paio di scarpe.

- Ho visto (chi?) Luigi.

Ho andato (cosa?)Sono andato (dove?) al cinema.

The third verb (andare) is clearly supported by essere.

As mentioned, some verbs don’t support an object (they are “intransitive”), but they need avere nonetheless. I suggest you to learn them by heart. Here’s a list of 30 important Italian intransitive verbs that need avere with the Passato Prossimo.

This list is incomplete, but it’s good enough for beginners.

Some examples.

Essere

- Sono andato al cinema

- Sei tornato presto

- È finito il film

- Siamo venuti a trovarti

- Siete tornati tardi ieri sera

- I bambini sono cresciuti

Avere

- Ho visto un film interessante

- Hai comprato delle scarpe nuove?

- David ha capito il passato prossimo

- Non abbiamo pulito la casa

- Avete salutato la nonna?

- I ragazzi hanno giocato bene.

Please try the quiz and let me know if you have questions.

LOADING QUIZ…

Carlo Carrà – Le figlie di Loth – 1919

MART, Museo di arte moderna e contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto

Why is it “Le mie figlie adolescenti” and not “adolescente”?

Perché adolescente è singolare, adolescenti è plurale.

Well I thought Michele was female and some of my e’ weren’t recognised as such and I thought divorziare would be considered a change. That made me a little cross

You can retry the quiz. Unfortunately the accents are a bit off and the software doesn’t speak Italian. Ciao.

It was petty of me to complain when you do such good work. Every mistake is a learning experience, I’ve been told. Thank you so much for all the material you put up:)

You are welcome. Keep adding your comments. For the record, Michelle is Michela in Italian, Michael is Michele. The choice wasn’t random in this case. Ciao.